Center Dance Ensemble

Choreographer: Frances Smith Cohen

Everyone loves a good opening. Here, Fran Cohen has given us a great one.

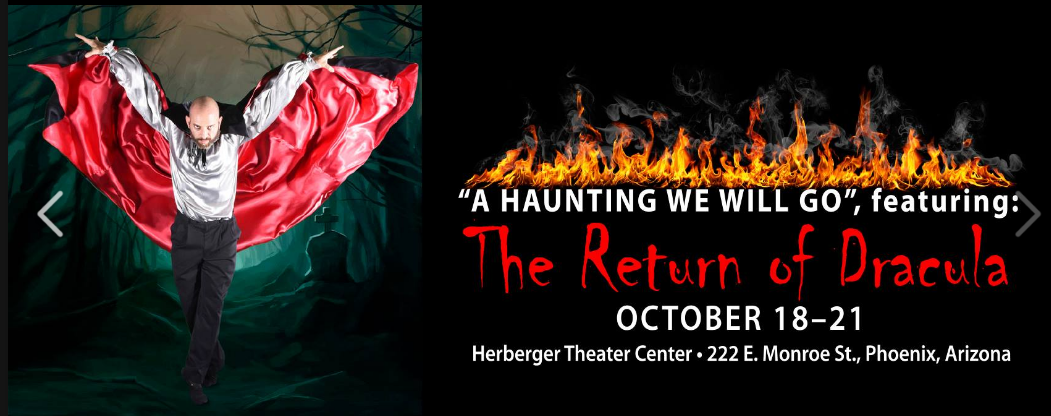

The lights come up on the stark, seemingly solo image of Dracula, dramatically lit in all his caped glory. The pulsating, bat-like motions of his cape-draped arms, with full reinforcement from the score, impart a deep sense of foreboding. The moment is potent with as-yet-undisclosed meaning as his every winged motion is mirrored by the barely visible dancer behind him. The big reveal exposes the duality of his character as the Count and the Beast simultaneously command the stage. It’s an inspired and beautifully executed piece of work.

The costumes, which are impressively elaborate and faithful to some uncertain historical period, give the production a sense of grand scale. The accompanying score is rich and immersive. Just let someone break into song and we’re at the opera.

The printed program, for those in the audience inclined to read it before the lights go down, attempts to give some plot guidance but no one is really focused on that as a full cast of characters work out the story on stage. What do you have to know, really? It’s Dracula. Somebody’s going to get bit. Judging from the opening, we’re going to love it.

The program reached a point where the visual narrative was perfectly bookended. The much-diminished Dracula’s dying swan was a touching and tragic reflection of the powerful, bat-like motions of his winged arms in the opening. The story arc from life to death was complete. It was an energetic and emotional journey and this was a powerful and ultimately satisfying ending. Except that it wasn’t the end.

As an audience, we went from beginning to climactic ending, then on to another beginning and climactic ending that wasn’t really the end either. Obviously, the choreographer had a larger story to tell but in the process, the audience never quite knew where we were at or when it was really over. Until it was. It was like a fireworks show, when you get a big burst of multiple explosions and color and then a lull and everyone thinks – “Was that it?” “Is it over?” “I mean, it could be…” – but then another rocket blazes and we’re off again.

Film and television have solved this long ago by perfecting the cliff-hanger – a dramatic moment that begs for resolution but makes you wait. That effect, of heightened interest, giving way to suspense and anticipation, didn’t happen here. The liability of having multiple climaxes that really feel complete unto themselves is that, if you follow them with more story, you end up with an equal number of anti-climatic moments, which can be deflating. “What, there’s more?”, “Why?”, “What’s this about?” With film, television and plays, you have a sense of character development and plot. Actors can expound on their situation with speeches full of exposition to let everyone know where we are, where we’ve been and where we’re going. Then, even if the hero dies prematurely, you know that can’t be it, the story simply can’t end there and, sure enough, it doesn’t.

By comparison, all dancers get to do is move their bodies through the air. With dance, we don’t necessarily know with certainty what the story is or where we are in it or if there even is a story. Without resorting to scantily clad ring girls walking around with cards to tell us what round it is – if it looks and feels like it’s over, it’s probably over. The Return of Dracula didn’t feel like a conventional long dance piece that was simply broken into several movements. This is hardly a fatal flaw in an otherwise brilliant and ambitious program, but it does point up the limitations of the form. Dance is not inherently capable of communicating a novel-length narrative, and seven scenes may be a few bridges too far. The Return of Dracula is a visually rich, bold, ambitious, fairly literal story, replete with subplots and character arcs that has three or four absolutely terrific endings. Including the real one.

Viewed Re/Viewed

Recent Comments