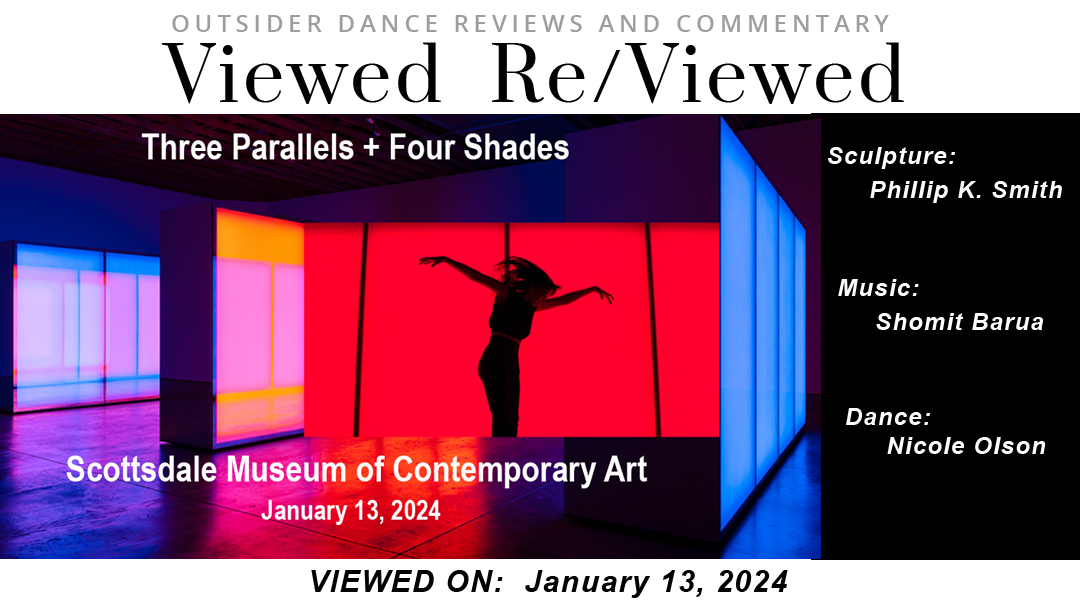

Three Parallels + Four Shades is an artistic collaboration sponsored by Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art (SMoCA). It celebrated Phillip K. Smith’s Three Parallels, a large-scale, site specific work incorporating light and color which was ending a year-long run as a featured exhibit. This ambitious, collaborative effort assembled luminaries in each of three disciplines – Scupture, Music and Dance. The resulting program involved a presentation from each of the three principal artists, who explained their methodology and how it related specifically to this exhibit and this evening’s collaboration. The evening concluded with a dance performance, Four Shades, choreographed by Nicole Olson, incorporating each of the three artistic elements, including the score, Four Shades, by composer, Shomit Barua.

Sculpture

Sculpture: Three Parallels

Artist: Phillip K. Smith lll

Three Parallels is a very descriptive title for this sculptural installation ending its year-long run at the Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art. However, if you haven’t seen it in person, it gives you no concept of scale. Imagine three rather narrow shipping containers placed side by side at a distance from each other (in parallel) in a cavernous hall and you’re somewhere close. This work is not part of an exhibition, it IS the exhibition, creating its own environment. Each element is roughly three feet wide, sixteen feet long and nine feet high. My eyeballs have not been calibrated recently so measurements are approximate. Each is comprised of reflective end panels, with the sides composed of four tall glass or acrylic panels which are independently backlit by a programed variation of four different shades of light. You are immediately struck by the color, as each section glows and fades, providing a strong secondary illumination of the space. You are free to wander between and around them, bathed in a rather beautiful glow emanating from either side.

These were lovely colors and the installation made for a rather pleasant experience, but for me it was pretty much limited to that. It wasn’t something I would be motivated to spend much time with. People are very divided on what they consider good or great art. Standards and styles are impossibly varied and perception irrevocably subjective. Ultimately, Eye of the Beholder is the only true thing about art. An artist friend of mine once said, somewhat wryly, that anything can be art if you make it big enough. After many years of observing art, I have come to the conclusion that she wasn’t wrong. Size really does matter. An art object on a pedestal can be observed with some interest. Enlarge it to the point where it commands the center of the room and it becomes amazing. Expand it many times more and, at some point, it becomes awe-inspiring. Pure scale has an outsized effect on our perception – pun intended.

My own experience with architecture, construction and fabrication left me less impressed with these simple structures than others might be. There is an ancient Greco Roman saying, “The idol makers do not worship”. I guess if you had just carved a statue of Zeus, you would want to get paid, not leave an offering. In essence, the more you know about how something is constructed, the less likely you are to be wowed by it. For those construction-oriented people, the simple geometry of these shapes and the fact that their most prominent feature is colored light panels, makes them less exotic. Some of my old blue-collar buddies – smart, capable guys – would probably take the dimensions, get the specifications, ask you how many you wanted and give you a bid.

My take on Three Parallels was very personal. I viewed this installation primarily as a performance space. If, in doing so, I have reduced a highly regarded, nationally famous sculptor, justifiably credited with some amazing works, to a set designer, I mean no disrespect. That is just about me, my peculiarities and proclivities, and about this particular evening. I was there to see some dance.

Music

Score: Four Shades

Additional Music: Mermaid Soup is a Bowl of Melted Ice Cream

Composer: Shomit Barua

As people randomly filtered into the space, music by composer Shomit Barua was being played, at volume, while they settled into the temporary seating provided for the presentation. Only after the fact was it apparent that this particular piece was called Mermaid Soup is a Bowl of Melted Ice Cream. In the meantime, it was an unusual track and an opportunity to actually be able to sit and listen to the composer’s music without the accompanying distraction of a performance. Someone more musically sophisticated than I might have had a very different experience, but for me, listening to this work gave me the impression of a linear journey, abstract, progressing melodically but with no discernable repeating motif. Here again, I refer you to my musical limitations.

While this was obviously pure electronica, uniformly intense, and in the beginning at least, something just this side of thundering, I was also aware of layers and layers of instrumentation which became more apparent as the piece progressed. Besides the thumping percussion from no human drums there were hints of strings and brass and even small orchestras that announced themselves and faded back into the driving beats like some hybrid cross between a locomotive and a moving melodic feast. I thought I detected rhythmic elements from South Asia or the Middle East, indistinct vocalizations and occasional solos intermingled with the omnipresent percussion.

When the soundscape suddenly changed, it went to another place altogether. There was a dramatic shift to something more arpeggiated, an atmospheric electronica. It was not looped, exactly, but repetitive, with subtle variations, like a rushing stream that occupies the background with a perpetual sameness until you enter into it and begin to listen more closely to the burbling and tinkling of which it is composed.

I had an opportunity to speak to Shomit Barua briefly after the performance and he smiled indulgently at my descriptions of Middle Eastern rhythms and mountain streams, disavowing any specific intention and insisting that he worked intuitively, responding only to what felt and sounded right – which I suppose makes sense if you’re creating abstract, ambient soundscapes.

So, Barua created what he created and I heard what I heard. Maybe all music is some sort of audio Rorschach test – all the more believable since music and sound trigger us at such a subconscious, emotional level. Performances of all types are acutely aware of this phenomenon and utilize it with great deliberation and effect. Vision is a factual thing – it is sound that informs how we feel about what we see.

And so it was with Four Shades, the score for this evening’s collaboration. As the performers took to the floor and the music was absorbed into the dancers’ bodies, it crept from my frontal lobe down into my tiny lizard brain where I sat, eagerly staring out of the window, progressively unaware that it was the score that was driving the bus.

Dance

Title: Four Shades

Company: NicoeOlsonІMovementChaos

Choreographer: Nicole Olson

Performers: Jordan Clark, Tyler Hooten, Nick McEntire, Nicole Olson, Zephyr Tuipulotu

Meandering through the Scottsdale Museum trying to find the performance space, nothing really prepared me for turning the last corner and confronting the cavernous area (I’m not sure you could call it a room) housing the three glowing monoliths that comprised the Three Parallels exhibit. My immediate thoughts would amount to a bulleted list, but most immediate and most relevant to the purpose of this review is, “How the hell is this ever going to work?”. The space was enormous. There was no apparent seating. The sculptures, by the very nature of their size and orientation, obstructed sight lines from every position. My first words were, literally, “What the hell?”.

Nicole Olson is no stranger to site-specific work. This was not her first rodeo and the very fact that she and her company, MovementChaos were performing meant that, by rights, it should be excellent. I just had no idea how. I wandered around and in-between the glowing walls created by the exhibit. There really was no front or back in this space but I finally settled on a position aligned with the direction of the parallels, facing the base of the central sculpture, that would allow me to see down the length of the spaces on either side between the two adjacent structures. I figured this was as good as it was going to get and, unwilling to stand for the duration, I dragged over a folding chair from the outlying presentation section. I claimed my spot, and as people gathered to stand along the exterior walls surrounding the exhibit, I was mindful of their even more limited view. The entire space was a confusion of variously compromised site lines. I had done what I could. The rest was up to Olson.

Right after the question, “How can dance possibly happen here?” was “What could it possibly be?”. A site-specific piece should not just be dance performed in a particular location. It should reflect and respond to the specific characteristics of the site. It should have a reason for being there. The ultimate test is that the same performance would be inappropriate or even impossible in a different environment. So, in this expansive space, with these huge, slick, illuminated constructs – what form could this performance take? Abstract? Impressionistic? Geometric? Certainly not emotional, in the way that we understand that in dance. In fact, it was none of those. Olson’s Four Shades, as best as I can characterize it, was celebratory.

It was also extremely episodic. It was constructed of moments, glimpses of this and that and something over there – sometimes together but often disparate, not all visible at once and certainly not from every angle. I was grateful for my location, convinced that this was the sweet spot. The illuminated corridors were too tempting for a choreographer and contained much of the most significant movement. Still, there was movement everywhere – perhaps not all at once, but at some point, every corner and corridor was covered.

I have often questioned the role of running in dance. Certainly there are times when it is consistent with the performance – dramatically entering or exiting the stage, getting from stage left to stage right, quickly closing a gap – but running for the sake of running, particularly running in circles, usually confounds me. It is a frequent element and almost always seems unmotivated to me, besides being one of the least dancerly movements. It’s certainly not as impressive for the audience as it seems to be important to many choreographers. This evening, however, running was not just motivated by the choreography, it was essential to the space.

Sporadically, the performers would dash around the circumference of the installation, either individually or en masse. This accomplished several things. It created a sense of energy, it provided moments of interesting, unexpected contrast with a momentary blur of a performer dashing past an unrelated series of movements and, most of all, it was a performance element, visible no matter where you were located in the audience, that allowed the company to fully engage the entirety of this impossible canvas.

I said that this performance was celebratory, and it was. Describing or defining that is difficult, but you know it when you see it. It was there in the uplifted faces, the expansive gestures and an undeniably joyful attitude. There was one rather quizzical exception where two figures rolled horizontally across the floor between structures for a seemingly interminable distance, but otherwise the movement and energy seemed to reflect the colorful positivity of this environment. There were some seemingly spontaneous danceathons and a very memorable segment with the entire company, rolling deep, swaggering and styling down a luminous walkway.

Reflection was a recurring theme, and by working with the simultaneously luminous and reflective qualities of the sculpture’s surfaces, Olson managed to capture one of the essential characteristics of the installation. Dancers, facing opposing sculptures, would make large gestures to their reflections in the surface, then, as a variation, they turned to face each other and synchronized those gestures with their counterpart. As simple as these gestures were, they represented the essence of site-specific choreography – in this case, reflecting reflection. There was a terrific expansion of this theme when the entire company engaged in a mirroring segment – with a twist. We’ve all seen mirroring routines – two performers face each other and accurately mimic each other’s gestures as though they were looking in a mirror. This was on another level.

In this segment, in my imperfect recollection, it was almost like they were beating on the illuminated surface, though I’m certain they never actually struck anything. This was an extended sequence, with everyone’s hands moving in synchronization. But here’s the catch. They were doing this back-to-back, and even those facing each other were separated by the massive central sculpture. No one had a direct view of anyone else, and yet the synchronization seemed perfect. This was a magic trick I simply couldn’t figure out. Yes, there was the score, but it felt linear, non-melodic – you couldn’t exactly jump in on the chorus, and this sequence had to start and stop simultaneously. Is everyone just counting? Seriously, this happened a long time from anywhere – that’s a lot of beats. Did the company huddle together before the performance and synchronize their internal clocks? What? Curious audience members want to know.

Maybe the best dancers really are just that good, and tonight Nichole Olson and her company, MovementChaos, demonstrated that they were. As a choreographer, Olson had just taken on what was easily the most difficult performance situation I can remember. SMoCA presented her with a gorgeous, spectacular, nightmare of a site and she rose to the occasion. Even her extensive experience with site-specific performance could not have prepared her for the unusual features and sheer logistical challenge that this represented. Only her instinctual ability to address her environment and respond to its characteristics, reflecting them and finding equivalents in her own physicality could have made this possible.

Viewed Re/Viewed

Recent Comments