Company: Ballet Arizona

Choreographer: Annabelle Lopez Ochoa

Performers: Leticia Endler, Helio Lima, Alli Chester, Katelyn May, Cheyenne You, Luis Corrales, Atsunari Matsuyama, Randy Pacheco, Ethan Price, Luis Olivera, Serafin Castro, Nayon Iovino, Trey Puckett, Gabriel Wright, Ricardo Santos, Greg Trechel, Erick Rojas, Marco Giuriato, Jordan Islas, Brooke Bendick, Demitra Bereveskos, Lindsay Camden Rachel Gehr, Genevieve Heron, Eastlyn Jensen, Katherine, Loxtercamp, Erin Mesaros, Natalie Ramirez, Alison Remmers, Isabella Seo, Renee Spaltenstein, Sarah Diniz, Students from The School of Ballet Arizona

Introduction

The tumultuous relationship between Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera was central to the mystique surrounding these artistic giants. It’s a story that we, who dabble in the art world, think we know – however imperfectly. Certainly, in the case of Kahlo, her passion and very real emotional and physical pain fueled an artistic temperament that was expressed in the arresting imagery and colorful flamboyance that characterized her work and drove it to international recognition.

The prospect of (of all things) a ballet (a ballet!) centered on her life was simultaneously too outrageous to be taken seriously and too intriguing to ignore. How can a life, lived large in the visual arts, possibly be depicted in music and movement? I immediately booked a ticket for Frida, motivated far more by the practical necessity of getting an answer to that question than “seeing a ballet”.

And so, I slipped into Symphony Hall on opening night, failing entirely to blend in with the fashionable attendees – who I prefer to think presented themselves so well, less out of vanity than respect for the occasion.

I have long since accepted the fact that, even if I possessed the attire, no finery would ever conceal my blue-collar, small town roots, and this evening, given the practical purpose of my attendance, my surrender to my native state was complete. I showed up in my broken sandals, with an ill-fitting sweater that was unable to fully conceal my Carhartt pocket tee-shirt from Tractor Supply. As I took my place among the off-off center bargain seats, I reminded myself that I was there to see, not to be seen. And as the lights went down and the curtain rose, blessedly, my self-consciousness began to melt in the darkness and the unfolding magic. Just as serfs and princes, living under the same sky, may have their imaginations enticed by the same shape-shifting clouds, the starlight from the stage illuminated both the worthy patrons and this poorly-shod, curiosity-driven schlump in the cheap seats.

Production

Frida opens on a scene from the Day of the Dead, replete with a cadre of skeletal figures. I don’t think Northerners, with Halloween as our only reference, who have long since dismissed Halloween’s pagan origins and even its “all hallows” sainted Christian usurpation, can every get beyond the candy and costumes to fully understand the deep spirituality integral to this quintessential Mexican holiday, which recognizes the ongoing relationship between the living and the dead. This opening scene was presented as a touchstone for the young Frida Kahlo, and from here, the production never surrendered its embrace of the surreal in illuminating her life story.

Early in her life, Kahlo suffered a severe, life-altering injury. “Hit by a bus” is the common conception that I am familiar with, and here we saw a representation of busy street traffic that could suggest this. I was really taken with the props created for this scene. These were two-dimensional, bent-pipe, representations of various vehicles. Each of these imaginative, loosely interpreted “vehicles” was, in my mind, a creative sculpture – in any other context, a worthy piece of whimsical art. This artistic originality was consistent with the ethos of the subject matter, and I thought the fact that they were openly (and convincingly) pushed back and forth across the stage, was in the best tradition of experimental theater.

The staging used was minimal, but versatile. An enormous cube in the center of the stage could be a backdrop or a dramatic, elevated platform, and was an essential visual element in the major transitions. When the context demanded it, a short, tri-fold wall could be opened up to reveal specific environments. In particular, it served as a mechanism to focus our attention as Frida’s character occupied various iterations of this device throughout the program. The background graphics were always more suggestive than literal, but somehow, we always got the point.

Initially, this represented a place of recuperation for the badly injured Frida and it was in this context that we were introduced to her spirit animal or alter ego, a deer. This performer was identified primarily by a set of antlers, but her movement helped create the illusion with the careful rise and placement of her legs in her gingerly approach to Frida, augmented by her mincing hands and the audible stabbing of her pointe shoes on the stage, suggestive of the sound of hooves – a sterling example of a dancer/actor creating and projecting a character. It quickly became apparent that the presence of the deer brought succor and hope to the practically immobile Frida, and we easily became emotionally attached to this creature.

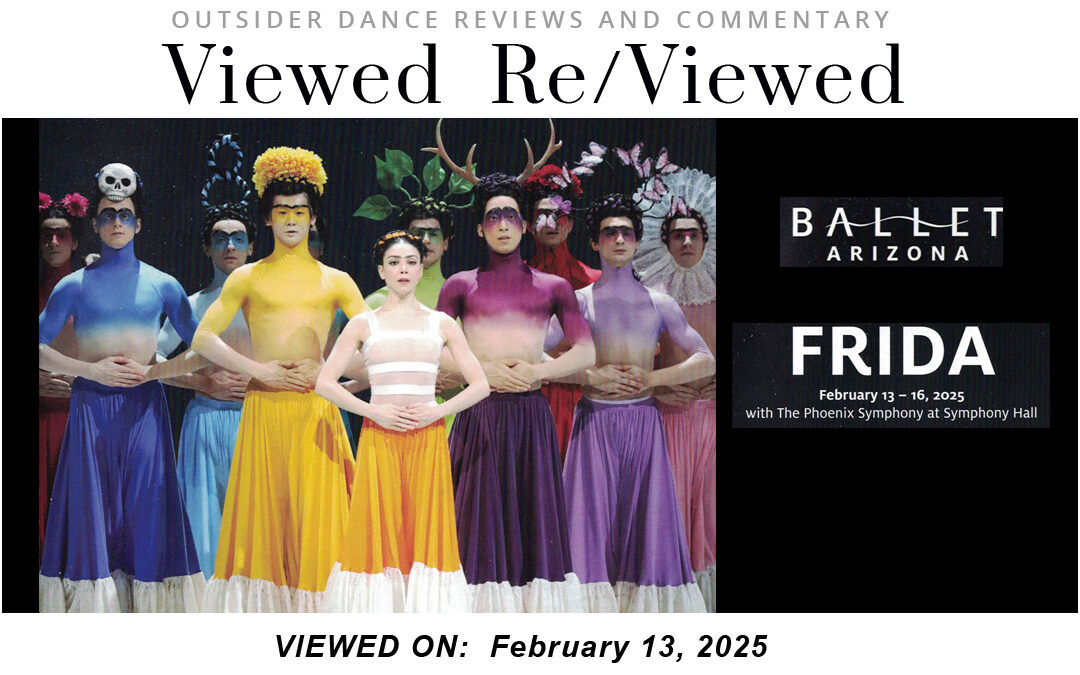

A dramatic ensemble, which was identified as “male Fridas”, flowed in and out of the production. Their colorful traditional Mexican skirts, body paint and creative headgear gave them almost complete command of the stage whenever they were present. This was an interesting artistic choice. They were a visual feast and purported to embody her self-portraits. While I thought I could see some of the references, I couldn’t help but wonder if they weren’t also a nod to Kahlo’s reputed bisexuality. Whatever they represented, they were beautiful, easily the dominant visual aspect of the production and as close as we were going to get to Kahlo’s paintings.

The character of Diego was not introduced immediately and took some time to develop. I thought I detected a bit of padding at his midriff, perhaps a suggestion of a paunch in keeping with our images of the historical Rivera, who was portrayed here as a vibrant, energetic character as befits the man. The duets between Diago and Frida played out an arc of passion, indifference, betrayal and reconciliation that characterized their tumultuous relationship. As dominant a figure as he was in Kahlo’s life – in this telling, Diago remained a secondary character. Frida, the ballet, was singularly about Frida Kahlo, with everything emanating from her perspective. As an audience, Frida’s relationship with Diago was something we witnessed along the way as we traveled deep into Kahlo’s psyche – a journey into magical realism, suffused with suffering, interrupted by brief moments of brilliance and beauty.

In this magical world, beneath choreographer Annabelle Lopez Ochoa’s unblinking gaze, the silent, secretive bits could be screamed out loud. In pursuit of the hidden truth, she constructed a scene so raw and visceral that it defies description. Here, the whispered rumors of Kahlo’s multiple abortions and miscarriages, which were a cruel aspect of her infertility, were brazenly enacted by the skeletal death figures, one of whom pulled, hand over hand, an endless stream of gore from the loins of Frida’s supine body, arched in agony. Suddenly, the entire stage was suffused with this imagery – everywhere, the blood, the gore, pervasive death and endless pain. A moment so brazen and profound it could not be immediately comprehended and left the audience stunned.

However, not every significant moment was a product of over-the-top, surreal drama. Sometimes I think ballet is like professional figure skating. Beautifully costumed, world-class athletes moving with consummate grace to swelling music. And we, the audience, become focused on the impossible leaps and impeccable, seemingly effortless landings, the artistry irrevocably bound to the sheer athleticism of the performers. But there were moments in this production where the most powerful emotions were conveyed with absolutely the least movement. So it was with Frida’s uncontrollable tremors in her leg, or a scene after her accident where her limbs hesitated and struggled to articulate properly. And, most memorably, in one telling scene, with Frida’s body impossibly hunched over, collapsed on itself, contorted in total surrender into a frozen tangle of pain. Even the costuming contributed, as in those moments where Frida was reduced to flesh-toned tights and we felt her naked vulnerability. Yes, this was dance, performed at a high level, but there was at least equal emphasis on conveying the emotion inherent in the moment.

I would be remiss to not mention the exotic bird, a beautifully costumed, fantastical character/creature of fairy-like delicacy, whose occasional appearance always brought with it a light, joyful presence and a shining ray of hope – a welcome respite among so much tragedy and, fittingly, emblematic of the survival of Frida’s fierce, artistic spirit upon her inevitable death at the finale.

Conclusion

One of my big issues with ballet, especially the classics, is the insulting simplicity of the storylines. But this was no fairy tale, all dressed up for the dance. Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera were real, live people who still exist in modern memory. Larger than life, perhaps, but flesh and blood nonetheless. Their lives and reputations, however mythical, needed to be grounded in a unique sort of reality that maintained their humanity while still allowing room for creativity and imagination.

In accomplishing that, this entire program displayed a deep respect for its subject. Frida, the ballet, was unblinking in the face of tragedy and moral ambiguity. Always extravagant, but never glossy. A production that fully embraced the surreal without explanation or reservation. This was an artist’s life, rendered by choreographer Annabelle Lopez Ochoa, as art itself – in one of the most improbable and beautiful ways possible.

The Practical Impossibility of Praise

It should be apparent to all who may read this, that I was very taken with this production of Frida, particularly its deft integration of artistic innovation and authenticity. However, heaping my poor praise on its creators – whether it be the choreographer, composer, costumer or lighting designer – would be an exercise in futility, my two hands clapping anonymously in an ocean of acclaim. All of these artists are nationally and internationally renowned for their craft. They collaborated here to do what they and few others can do – create world-class art.

All that remains to me, realistically, is my appreciation – which is personal, heart-felt, and the progenitor of lasting memories.

Viewed Re/Viewed

Les,

The fact that the great Art of Frida, using Ballet and as a trained dancer and teacher of Martha Graham technique, also some Graham vocabulary, compelled you to experience this, and then to allow such a deep unforgettable experience, proves to me that once again, AI robots in live spaces will not be taking over our jobs for probably a hundred years. The fact this Art touched in your words a, “blue collar small town roots » man, is enormous to me as a full time national over 35 years veteran Dance Educator and Choreographer. I too was deeply moved and forever touched by Ochoa’s creation and co creation of the other great artists. The use of battue to convey pain for instance, BRILLIANT! The fact our classics are indeed are insulting storylines has always been what I have strived to change in my own creations as well. Whether as a dancer deciding to be in a company performing works by choreographers who did this, or in choreographing long to shorter length Ballets. Here in Prescott, I strive to bring awareness to every walk of life of this Art amongst the 10 specialities I am versed in out of the thousands of Dance forms all equally important on our planet. After living all over this country for work, I find people are mostly from elsewhere in this small town, and hungry for great Art too. This does include locals who grew up here too though. Thank you so much for your exquisitely written review. It’s authentic and needed. Mary Heller – marychoreographer.com